Huge opportunities for Australian businesses in India says Jim Varghese

The Chair of the Australia India Business Council (AIBC) Jim Varghese AM gave a great presentation in Brisbane Tuesday last week on the huge opportunities for Australian businesses in India. He noted some striking demographic facts and highlighted how India’s healthy and well-proportioned population growth, which stands in stark contrast to China’s, is a good omen for future economic prosperity.

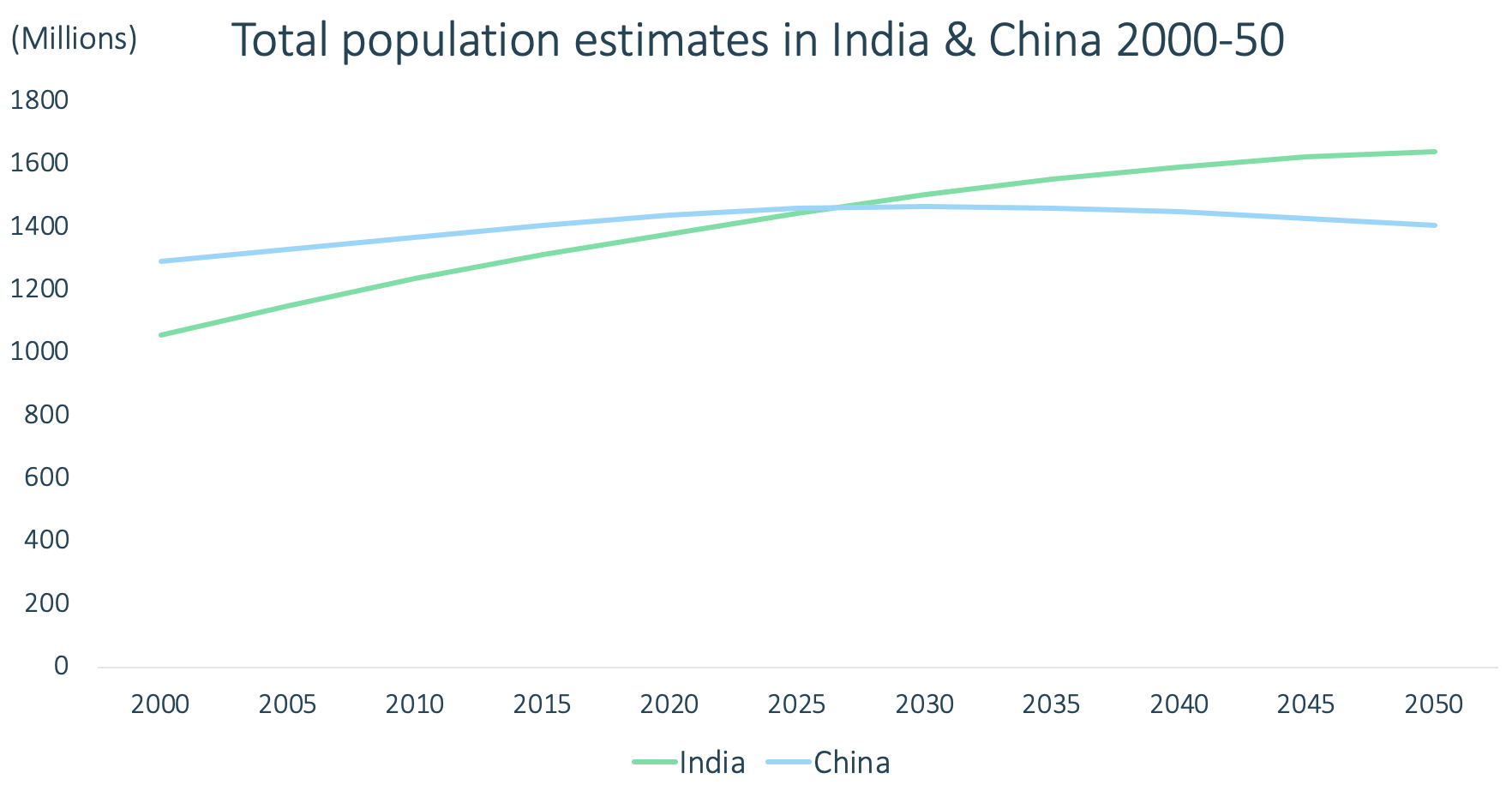

Firstly, India’s population is projected to overtake China’s around the mid-2020s (See below).

Source: UN World Population Prospects

Crucially, India is showing strong growth in the working-age population (15-64), which, if managed well, should be capable of supporting elderly and young dependants. Around the mid-2020s, India’s working-age population should overtake China’s, at just under 1 billion.

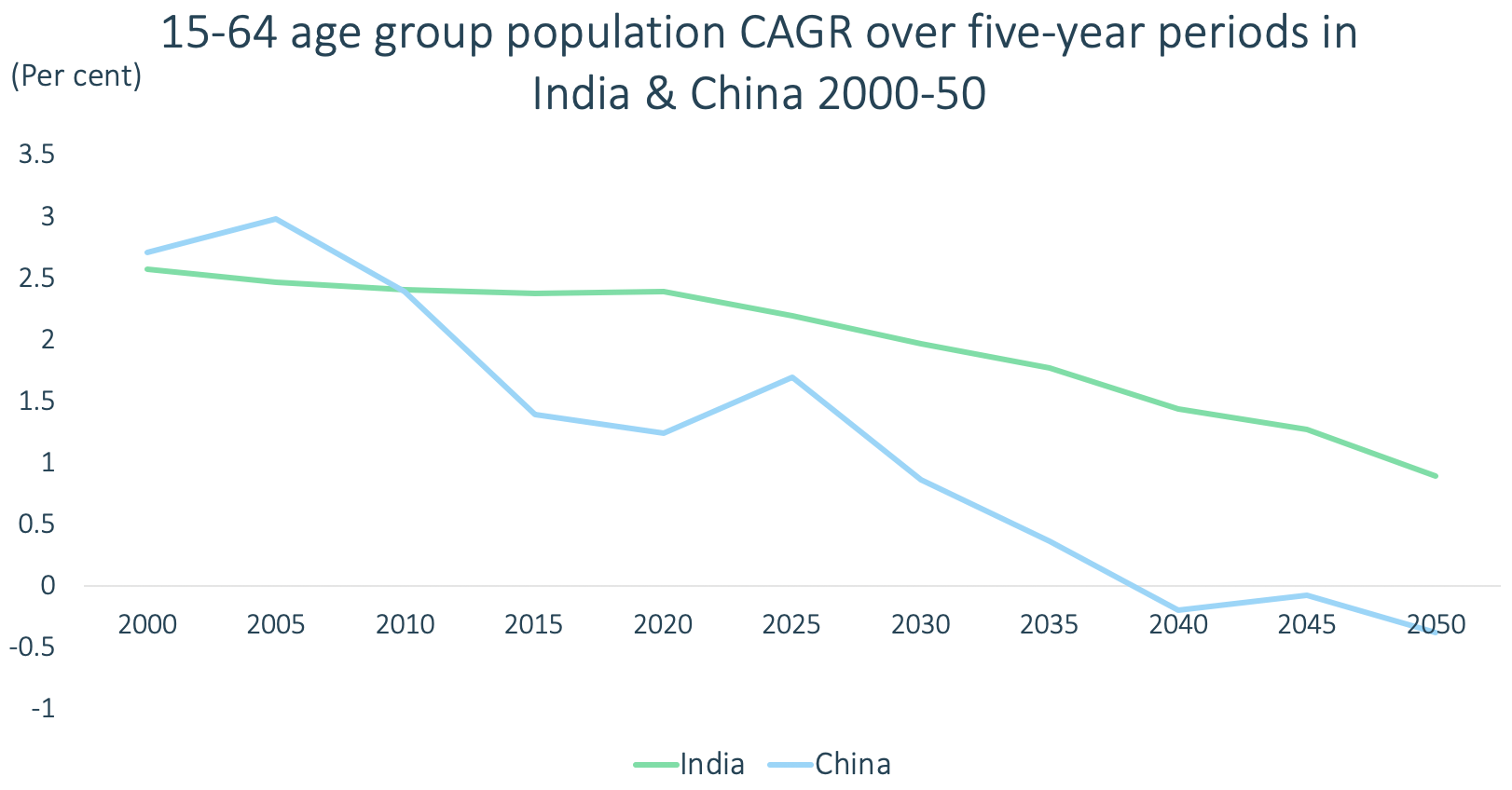

Perhaps more insightful, however, are the respective Compound Annual Growth Rates (CAGR) in China’s and India’s working-age populations. India’s CAGR estimates may be steadily falling, but China has been enduring a steep decline in the growth of its working-age population since 2005, which is forecasted to reverse in 2025 before descending even further. Moreover, China’s working-age population is expected to shrink year-by-year in 2040 and well into the future (See below).

Source: UN World Population Prospects

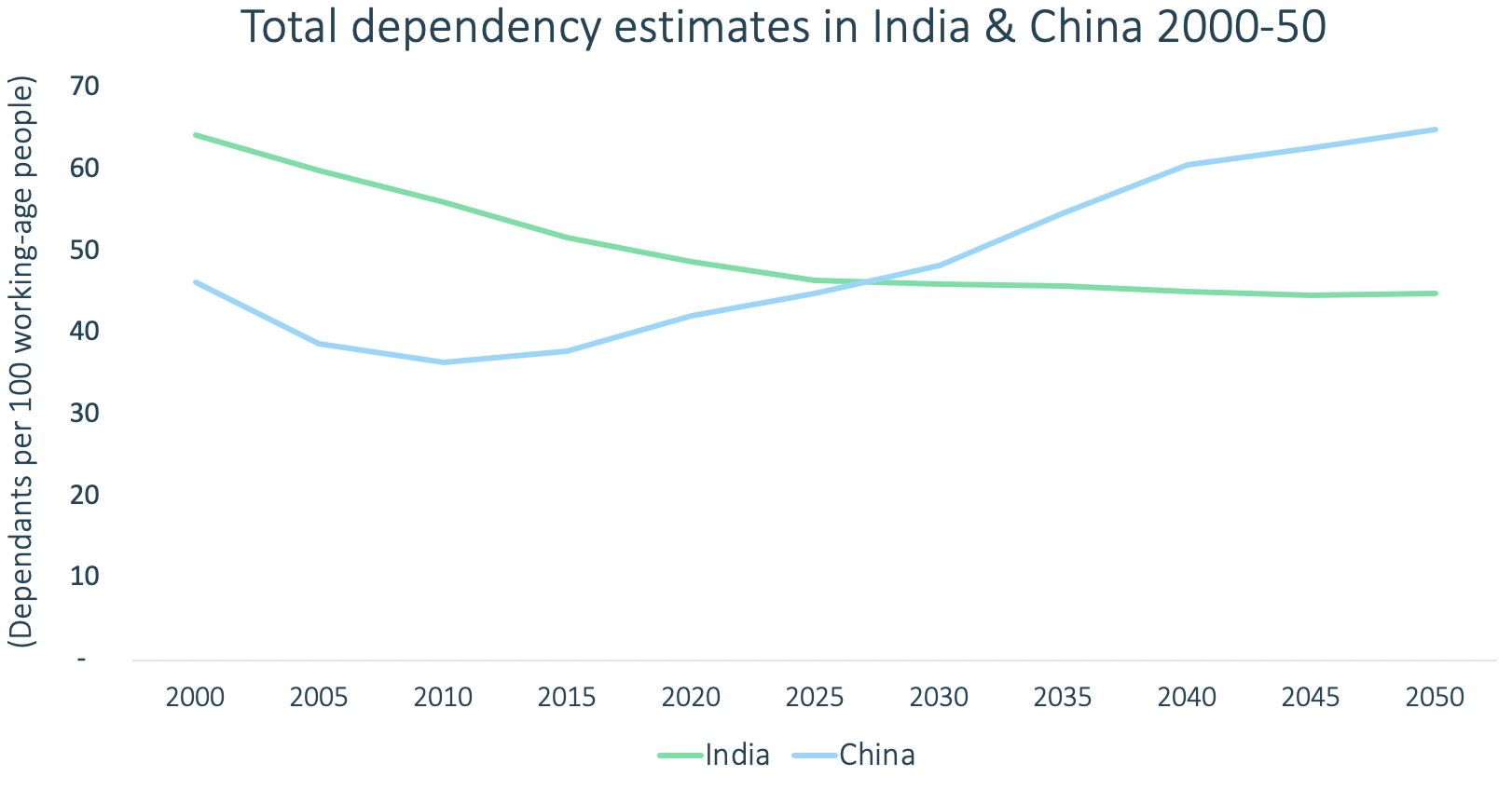

Therefore, what is often referred to as the “ageing population burden” should not be an issue for India until 2050 at least. Indeed, India should be able to tolerate growth in both the young and elderly demographics quite comfortably. The total dependency estimates are expected to remain at around 50 dependants (infants aged 0-14 and elderly persons aged 65+) per 100 working-age persons (aged 15-64) from 2030 onward. The same cannot be said about China; by 2050 there is expected to be just under 70 dependants for every 100 working-age people (See below).

Source: UN World Population Prospects

Importantly, strong demographics are not the only indicator of economic prosperity. Indeed, a healthy and well-proportioned population means nothing in the face of poor business prospects and low employment. However, even in this regard, India is showing great progress.

India recently jumped 23 spots to rank 77 out of 190 countries in the world in terms of “ease of doing business”. This is the result of a series of reforms pushed through parliament by Narendra Modi, India’s Prime Minister, that relaxed the environment around construction permits, tax thresholds, and international trade requirements. The World Bank’s India Country Director Junaid Ahmad recently noted that India’s “recent policy reforms have helped India improve the business environment, ease inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and improve credit behaviour”.

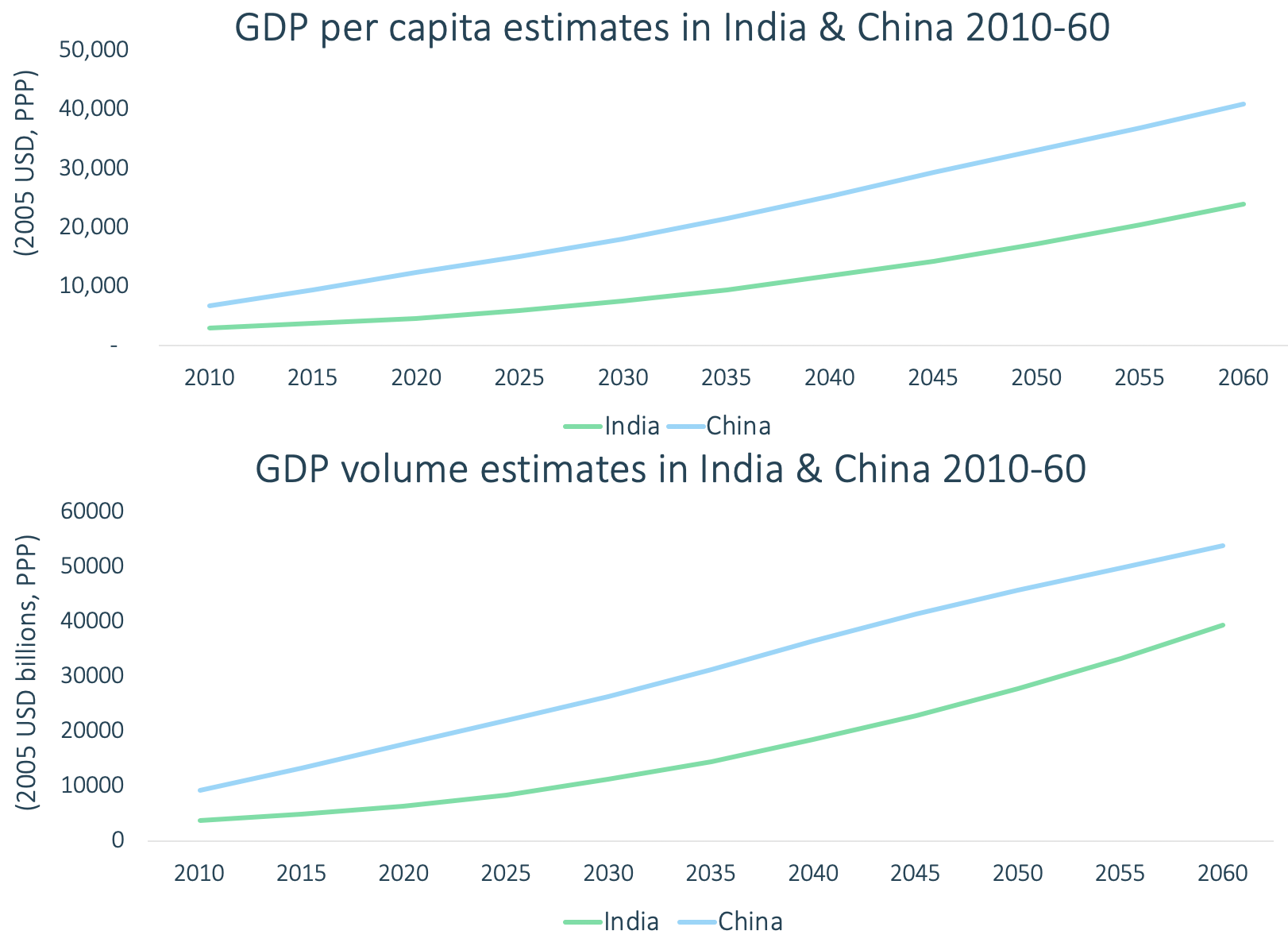

Despite an improving business environment, India is still expected to lag behind China in terms of GDP and GDP per capita (in $US 2005 PPP) well into this century according to the OECD’s 2014 long-term baseline projections. The OECD forecasts show that, despite considerable convergence in proportional terms, China’s GDP and GDP per capita will remain substantially above China’s. For instance, in 2015 India’s GDP volume was 36% of China’s, and in 2060 this figure is expected to increase to 73%. But China’s GDP volume will still be $15 US trillion (2005, PPP) above India’s in 2060 (See below).

Source: OECD Economic Outlook

So, what does the rise of India mean for Australia? Over the past 12 months, India has been Australia’s fourth-largest merchandise export destination ($17.4 billion), according to the ABS. China remains Australia’s largest merchandise export destination ($131,6 billion), but in the face of China’s slowing growth and a deteriorating global economic environment, growing trade connections with India could prove important for Australia’s continuing prosperity. This sentiment has been documented at length by Peter Varghese, Jim Varghese’s brother, in the India Economic Strategy to 2035 report he prepared for the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in 2018.

In particular, India will be in need of Australia’s commodity exports, including thermal coal, as it looks to develop its economy. Queensland’s large resources and energy sector will, and has been, benefiting from such demand. India is currently Queensland’s third-largest export destination. Various Indian companies, such as Adani, have already demonstrated an interest in doing business in Australia. At the seminar, Jim Varghese predicted that “India will need Australia’s coal for at least another 30 years” to support its economic development. Anticipating heavy criticism, Varghese defended Adani’s plans to build the Carmichael mine by pointing out that Adani is also a major investor in renewable energy.

Additionally, Australia is steadily becoming a popular destination for Indian students looking to study abroad. Indeed, India is the second-largest source of international students in Australia. From 2017 to 2018, the total number of Indian students grew by 24.5%, compared with 10.9% growth in the total number of Chinese students. In 2018, 12.4% of Australia’s international students were Indian, compared with 29% being Chinese. As in many other sectors, India’s growing presence in Australia is becoming increasingly clear.

Australia’s vocational education and training (VET) sector has a major opportunity to train growing numbers of Indian students, both domestically and in India. According to Varghese, Indian PM Modi said to him that Australia’s VET system was “second to none.”

Other than resources and education, Varghese noted several sectors which offer Australian businesses current and prospective opportunities with India, including:

- Agribusiness, once the Australia-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement is finalised, with Varghese commenting he wanted to see Australian farmers exporting mangoes to India, for example;

- Health, particularly for pharmaceuticals (e.g. see Australia as a drug discovery partner for Indian pharmaceuticals – Overview by Proteomics International);

- sport, rather obviously, as many of our top cricketers playing in the Indian Premier League (IPL) have discovered; and

- Tourism, as the Indian middle class grows and seeks to travel internationally.

Jim Varghese has brought India to the forefront of the conversation about Australia’s economic future, but the numbers really do speak for themselves. Despite its recent slowdown, India’s strong demographics and long-term growth prospects should play a key role in Australia’s continuing economic prosperity.

This article was prepared by Ben Scott, Research Assistant, and Gene Tunny, Director, of Adept Economics. Please get in touch with any questions or comments to ben.scott@adepteconomics.com.au.