What Would Adam Smith Make of Modern Australia?

“Capitalism has been hijacked by capitalists.”

That was one of the striking lines from my recent podcast conversation with Joseph Healy, former CEO and co-founder of Judo Bank and author of What Would Adam Smith Make of Modern Australia?

It’s a provocative claim. But Joseph is not anti-market — far from it. He describes himself as “unashamedly a capitalist.” His concern is not with markets per se, but with what happens when competition weakens, incentives distort behaviour, and the moral foundations that underpin a market economy erode.

The question he poses is a useful one: what would Adam Smith — often invoked as the intellectual godfather of capitalism — make of Australia today?

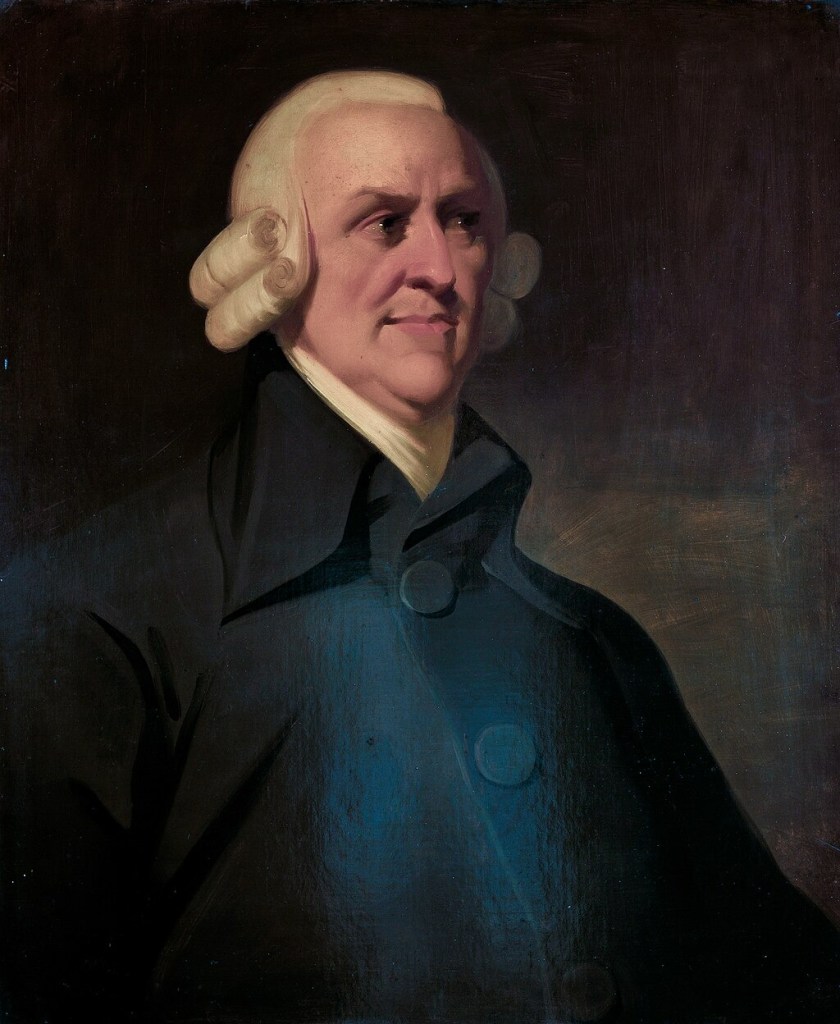

Adam Smith: Economist and Moral Philosopher

Smith is best known for The Wealth of Nations (1776), which defends trade, competition, and the famous “invisible hand.” But 17 years earlier, he wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a work that explored sympathy, virtue, and the ethical foundations of society.

Healy argues — and many scholars agree — that these two works must be read together.

Smith believed markets were powerful mechanisms for allocating resources and promoting prosperity. But he also believed that markets operate within a moral and social framework. People, he wrote, desire “to be loved and to be lovely” — that is, to be respected not only for their success, but for having achieved it honourably.

That distinction matters.

In our discussion, Healy made a simple but powerful point: there is a difference between asking “Is this legal?” and asking “Is this right?” The legal test is a low hurdle. The moral test is higher.

A market economy depends not only on price signals and profit incentives, but also on trust, reputation and norms of fair dealing. When those weaken, something important is lost.

Where Might Australia Have Drifted?

Australia remains a prosperous country by global standards. We are a successful trading nation, strong in resources and agriculture, and we have avoided many of the economic crises that have hit other countries.

But Healy argues that, beneath the headline numbers, structural concerns are emerging.

1. Weak Competition and Economic Rents

One concern is market concentration.

In sectors such as banking, airlines, food retail and energy, Australia has a small number of dominant firms. These industries are often highly profitable — in some cases, among the most profitable in the developed world.

High profitability in itself is not a problem. But if it stems from weak competition rather than innovation and efficiency, it may signal the presence of economic rents. Economic rents are extra profits that arise from market power or limited competition rather than genuine productivity or innovation.

Healy argues that when firms operate in “cozy” market structures, the incentive to innovate diminishes. The focus shifts to protecting profit pools rather than engaging in creative destruction. Consumers may face higher prices and fewer choices. And lobbying efforts can reinforce the status quo.

This is not an abstract issue. We discussed examples ranging from the banking sector to the debate over airline competition, where government decisions can materially affect market structure.

The broader question is whether Australia has been sufficiently pro-competition in its policy settings — not merely preventing further consolidation, but actively encouraging entry and contestability.

2. Banking, Housing and the Allocation of Capital

A second issue concerns the allocation of credit.

Healy noted that over the past two decades, Australian banks have shifted significantly toward household mortgage lending, with comparatively less lending to small and medium-sized enterprises.

From a private bank’s perspective, mortgages can be attractive: they are often perceived as lower risk and collateralised by property. But at a system level, this shift raises questions.

Australia now has one of the most highly leveraged household sectors in the world. While much of this debt is backed by assets, there is still exposure to housing market cycles and interest rate shocks. Moreover, when a large share of credit flows into property rather than productive business investment, it may affect long-term economic dynamism.

Banks play a privileged role in the economy. They are critical for capital allocation. Healy asks whether current incentives are leading to the most productive allocation of that capital.

3. The Disconnect Between Economy and Society

Healy’s most ambitious claim is that the health of the economy and the health of society may be drifting apart.

Economically, Australia performs well, with a relatively high standard of living. But on social indicators — educational outcomes, domestic violence, gambling harm, substance abuse — there are areas of concern.

Smith believed a prosperous economy should be matched by a healthy society. If economic growth coexists with widening inequality, declining educational performance, or erosion of social trust, that mismatch may not be sustainable.

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Healy to give Australia a “scorecard” from an Adam Smith perspective. His verdict: an A for trade, but a D for competition and a C+ overall — with a warning about the trajectory.

That is a sobering assessment.

Complacency vs Crisis

Without underplaying the significance of the productivity and cost-of-living concerns in the last few years, Australia has performed remarkably well economically over the past few decades. We are not in an economic crisis, and our institutions are holding up for now and are certainly under less strain than in the US.

But Healy sees a risk of “sleepwalking” into deeper structural problems — the proverbial boiled frog, unaware of gradual changes until it is too late.

I’ll admit that over the years I’ve become more open to the idea that issues such as weak competition and market concentration deserve greater scrutiny. That doesn’t mean embracing alarmism. It does mean being willing to examine whether our institutions and policies are evolving in ways that support long-term prosperity.

Where to From Here?

Healy outlines several areas for reform:

- strengthening competition policy,

- reassessing the scale and complexity of regulation,

- tax reform,

- rethinking corporate governance (which has been weak in Australia in Healy’s view), and

- investing in education and training.

Reasonable people can debate the details. But the broader question he raises is harder to dismiss:

Can a market economy thrive if its moral and competitive foundations weaken?

Adam Smith was not a simplistic cheerleader for business. He was a careful observer of human nature and institutions. His defence of markets rested on assumptions about competition, virtue and social norms.

Adam Smith

If those assumptions no longer hold, it is worth asking what needs to change.

I explored these issues in more detail with Joseph Healy on the latest episode of Economics Explored. If you’re interested in how Adam Smith’s ideas might illuminate modern Australia’s economic challenges, you can listen to the full conversation on podcast apps (e.g. Apple Podcasts) or using the web player below.

Gene Tunny, Director, Adept Economics

Published on 16 February 2026. For further information, please contact us at contact@adepteconomics.com.au or call us on 1300 169 870.