Should Australia “Make Things Again”? The Economics of Protectionism in a Changing World

Gene Tunny, Director, Adept Economics

First, I’d like to announce that Adept Economics is currently advertising a casual administration assistant position, with details available on Seek, for anyone interested.

Liberal MP Andrew Hastie’s recent call for Australia to “make things again” has reignited debate about the role of manufacturing in our economy — and whether protectionist policies could restore national self-reliance and pride.

It’s an issue that strikes a chord with voters and policymakers alike. Around the world, from Washington to Westminster, political leaders are questioning decades of faith in free trade and globalisation. But can Australia really turn back the clock on its industrial base? And would protectionism actually make us stronger — or poorer?

In a recent Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance livestream, I discussed these questions with economist John Humphreys, Policy Director at the Australian Taxpayers Alliance. Our conversation explored why the idea of “Made in Australia” has such political appeal — and why it often runs into economic reality. I also featured the conversation in a recent episode of Economics Explored.

The Political Appeal of Making Things Again

The phrase “make things again” taps into something deeply emotional. It evokes nostalgia for a time when Australian factories employed hundreds of thousands of workers, when Holden cars rolled off production lines, and when manufacturing seemed central to our national identity.

As John Humphreys pointed out, nostalgia is politically powerful. It appeals to blue-collar voters who feel left behind by the forces of globalisation and automation. Similar sentiments helped fuel Donald Trump’s rise in the United States and the Brexit movement in the United Kingdom. In Australia, it is re-emerging as a defining issue on the centre-right.

But the emotional appeal of “making things again” does not make it good economics. Before governments attempt to recreate old industries, it’s worth asking whether the world we remember still exists — or whether technology and trade have moved on for good.

The Economic Realities of Protectionism

In theory, tariffs, industry subsidies, and other protectionist measures can protect domestic producers from foreign competition. In practice, they are expensive and inefficient ways to do so.

John Humphreys explained that while a very small tariff might raise modest revenue with limited distortion, any tariff high enough to make a real difference to domestic producers would come at a steep cost. A “meaningful” protective tariff would push up consumer prices, reduce productivity, distort investment, and invite retaliation from trading partners.

The experience of the Australian car industry is a case in point. As I noted in my 2011 Centre for Independent Studies Policy Paper, Carr’s Car Cash, decades of tariffs and subsidies for local car producers provided little lasting benefit. Despite billions in taxpayer support, protection could not overcome Australia’s small domestic market and high production costs. In the end, assistance merely delayed the inevitable closure of the industry, while diverting resources from more productive sectors of the economy.

Subsidies and protectionist measures may save a few visible jobs in the short term, but they do so by imposing hidden costs on the rest of the economy — through higher prices, lower productivity, and reduced competitiveness.

Protectionism might be politically popular, but it’s economically self-defeating. It replaces competitive advantage with political patronage — rewarding the best lobbyists rather than the most productive businesses.

Security, Sovereignty, and Sensible Policy

There is, however, one area where the “Made in Australia” movement raises legitimate concerns: national security and economic resilience.

Both John and I agreed that it makes sense to think carefully about supply chain risks, especially given Australia’s dependence on China for key materials and manufactured goods. The pandemic and recent geopolitical tensions have exposed the vulnerability of overreliance on a single supplier.

Concerns about overreliance on a single country are not theoretical. China currently dominates global processing of critical minerals, including rare earth elements essential for electric vehicles, wind turbines, and advanced defence technologies. This has created what some analysts describe as a “chokehold” on supply chains. Arguably, Australia is responding sensibly — not by retreating into protectionism, but by partnering with allies to diversify production and processing capacity. The recent Australia-US Critical Minerals Agreement, along with new projects in Western Australia and the Northern Territory, aims to build a more resilient supply chain for these strategic resources while keeping Australia integrated in global markets. That said, I will closely monitor the outcomes of this agreement to ensure it does not veer into costly protectionism.

“Economic sovereignty” should not mean cutting ourselves off from trade. The smarter approach is diversification, not autarky. Australia should strengthen supply chains through partnerships with trusted allies such as Japan, India, and the United States — not attempt to produce everything domestically at great cost.

As the old saying goes, don’t put all your eggs in one basket. But that doesn’t mean you should start making your own baskets.

Automation and the Future of Manufacturing

Another central theme in our conversation was the role of technology. Even if we wanted to rebuild the old car industry, automation means those factory jobs aren’t coming back.

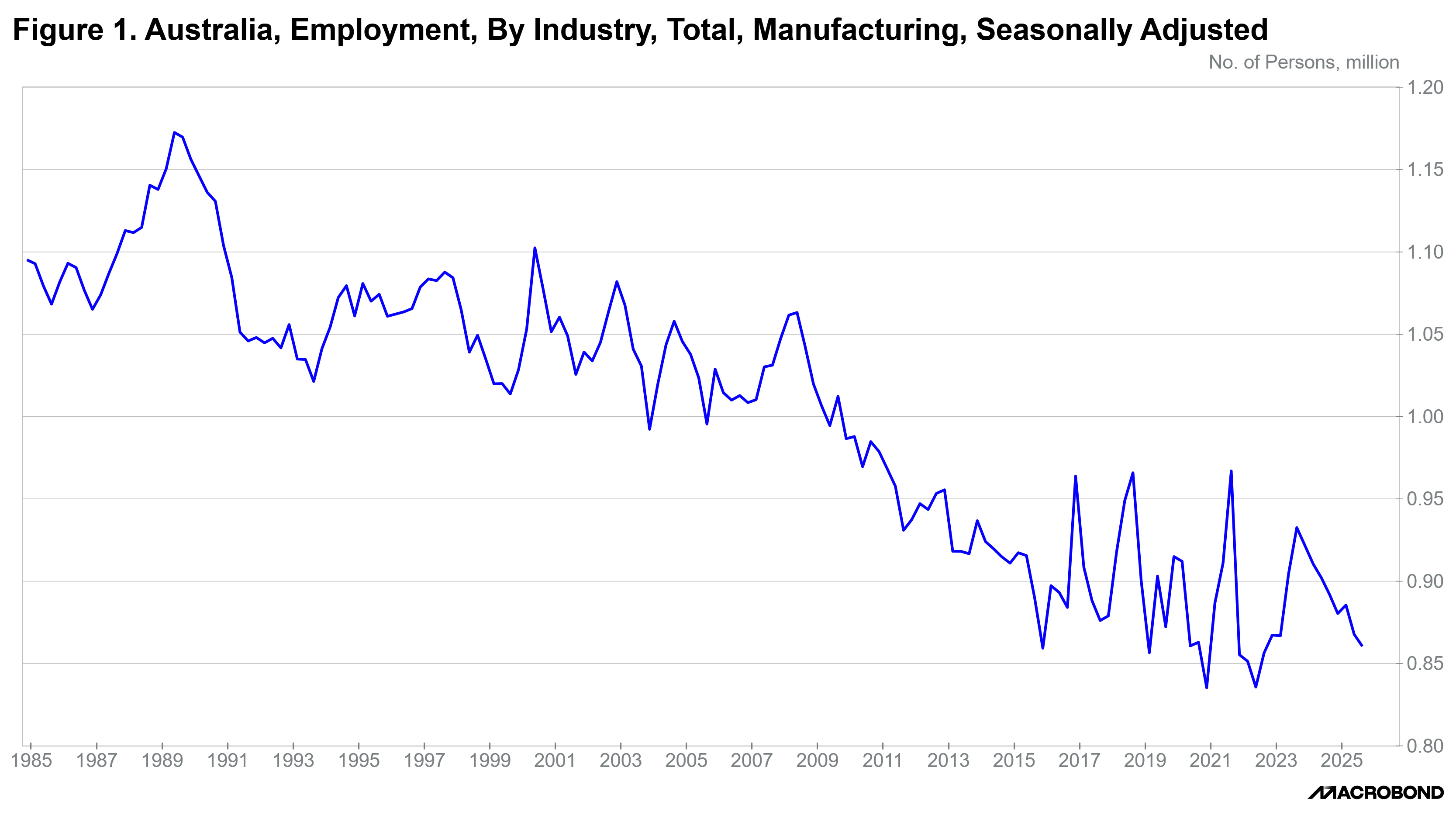

The decline in manufacturing employment has far more to do with technological change than with trade policy (Figure 1). Across the developed world, machines and software now do most of the work that once required thousands of people.

That doesn’t mean manufacturing has no future in Australia — far from it. The real opportunity lies in advanced, high-value manufacturing, where we already have world-class firms and comparative advantages.

Examples include:

- Quickstep, which produces advanced carbon-fibre components for Boeing and Lockheed Martin;

- RØDE, a popular brand of audio equipment, designed and fabricated in Sydney, for content creators;

- Cochlear and ResMed, global leaders in medical technology, and

- Electro Optic Systems, which designs precision weapons systems and satellite tracking technology.

These businesses show that Australia can still “make things” — but not the same things we used to. Success today depends on innovation, research, and skills, not protectionism.

Policy Principles for a Productive Australia

If policymakers genuinely want to boost Australian manufacturing, they should focus on productivity-enhancing reforms rather than subsidies and tariffs.

That means:

- Lower and simpler taxes to reward investment and entrepreneurship;

- Regulatory reform to cut red tape and improve competition;

- Reliable, affordable energy to support energy-intensive industries;

- Flexible labour markets that allow firms to adapt and grow; and

- Broad-based support for R&D and innovation that doesn’t pick winners.

These are the kinds of policies that raise the competitiveness of the entire economy, not just a politically favoured few.

Conclusion: Lessons from the Debate

The “Made in Australia” discussion highlights a core dilemma in economic policymaking: politics rewards protectionism, but prosperity depends on productivity.

It’s easy to understand why calls to “make things again” resonate. They speak to national pride and the desire for economic security. But Australia’s path to prosperity lies not in reviving industries of the past, but in fostering the industries of the future.

We can still make things — just not the same things we used to. The challenge for policymakers is to channel public enthusiasm for making things into smarter, forward-looking policies that lift productivity and keep Australia competitive in an increasingly complex world.

Published on 13 November 2025. For further information, please get in touch with us at contact@adepteconomics.com.au or call us on 1300 169 870.