Whitlam and the Economy: Lessons from a Turbulent Time

Fifty years ago today, on 11 November 1975, Australia experienced one of the most dramatic moments in its political history — the dismissal of the Whitlam Government. While much has been said about the constitutional and political dimensions, it is also worth reflecting on the economic management of the Whitlam years and the lessons that period still holds today.

This article draws on my chapter Whitlam and the Economy, published in The Whitlam Era: A Reappraisal of Government, Politics and Policy (Connor Court, 2022).

A Time of Economic Upheaval

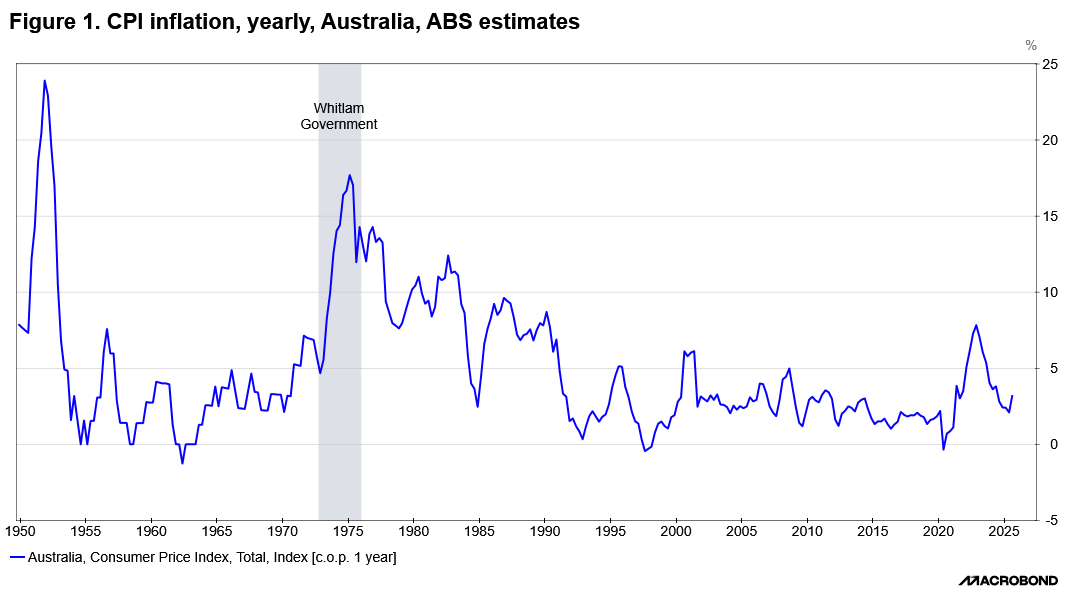

The Whitlam Government came to office in December 1972 just as the post-war economic boom was ending. By the time of its dismissal three years later, inflation had surged to 17 per cent (Figure 1) and unemployment had climbed to its highest level since the Great Depression.

Some of this was bad luck. The first global oil shock in 1973 upended the world economy, sending prices soaring and triggering what became known as stagflation — high inflation and rising unemployment occurring together. Yet Australia’s experience was also shaped by bad management, as the Government pursued an ambitious social program with insufficient regard to the economy’s capacity to absorb it.

Economic Policy Without Modern Anchors

The early 1970s economy lacked many of the policy frameworks we now take for granted. There was no independent Reserve Bank mandate, no medium-term fiscal strategy, and the exchange rate was fixed. Centralised wage setting and high tariffs further limited flexibility.

In that environment, policy mistakes were magnified. Treasury’s warnings about the macroeconomic risks of the Government’s expansive program — increased spending on health, education and social security — were largely disregarded.

Fiscal Expansion Meets Monetary Tightening

Nowhere was this clearer than in the clash between fiscal and monetary policy. In 1974-75, Commonwealth outlays rose nearly 20 per cent in real terms, one of the largest peacetime increases on record. At the same time, the Reserve Bank was tightening monetary policy to rein in inflation, pushing up interest rates and slowing credit growth.

As a result, fiscal and monetary policies operated at cross-purposes — government spending was adding to demand and inflationary pressure just as the central bank was trying to restrain it. Bill Hayden, who became Treasurer in June 1975, later described this as forcing the adjustment “by means of the much less equitable, blunt mechanism of monetary policy.” The OECD’s 1975 survey of Australia reached a similar conclusion, noting that higher interest rates were a major contributor to the downturn that began in 1974.

The Wage–Price Spiral

The Whitlam Government’s own pay policies added fuel to the fire. Acting as a “pacesetter” on public sector wages and conditions, it helped drive wage expectations across the economy. Combined with strong union power and a centralised wage-fixing system, this led to a wage–price spiral — average earnings jumped 29 per cent in 1975 while inflation eroded the gains. Industrial disputes were intense, with more than 6 million working days lost in 1974.

Some Sensible Measures — and Early Microeconomic Reform

To its credit, the Government did take some sound economic decisions. It revalued the Australian dollar three times in 1972–73 to address a large balance-of-payments surplus, and cut tariffs by 25 per cent to relieve supply-side pressures and lower prices. These moves also marked the early beginnings of microeconomic reform.

The Whitlam era produced several enduring structural changes:

- The Trade Practices Act 1974, the foundation of modern competition and consumer law;

- The creation of the Industries Assistance Commission, precursor to today’s Productivity Commission; and

- The breakup of the Postmaster-General’s Department and the creation of Telecom (now Telstra) and Australia Post.

These reforms, while overshadowed at the time by economic instability, helped shape a more competitive and efficient economy in the decades that followed.

An Enduring Legacy

From an economic perspective, the Whitlam Government’s major legacy was the permanent expansion of Commonwealth spending. The federal government’s share of GDP jumped from about 19 per cent before 1972 to over 23 per cent by 1975 — and it has never fallen below that level since. Programs such as Medibank (the precursor to Medicare) and free university education changed expectations of the government’s role in social policy.

More indirectly, the experience influenced later governments. The Hawke and Keating Governments, determined not to repeat the mistakes of the 1970s, placed economic discipline and structural reform at the heart of their agenda. As Andrew Leigh MP has observed, Labor learned that “if Labor were to govern for a long period – for a 13-year period rather than a three year period – it had to have economic discipline at its core.”

Conclusion

The Whitlam years stand as a reminder that good intentions in social policy must be matched by sound economic management. Fiscal discipline, coordination with monetary policy, and respect for institutional advice are essential if reform is to endure.

Half a century later, it remains clear that credibility in economic management is the bedrock of effective government.

Gene Tunny, Director, Adept Economics

Published on 11 November 2025. For further information, please get in touch with us via contact@adepteconomics.com.au or by calling us on 1300 169 870.